By Gwladys Fouche and Nerijus Adomaitis

OSLO (Reuters) – On a cold December morning in 1975, Soviet dissident Andrei Sakharov met a Norwegian diplomat on a Moscow street to hand over his acceptance speech for the Nobel Peace Prize, so his wife could read his words at the Oslo award ceremony he was forbidden to attend.

Nuclear physicist Sakharov was one of the Soviet Union’s most prominent dissidents, criticising the lack of human rights under Communist party rule, and the father of the Soviet hydrogen bomb who later campaigned against nuclear weapons.

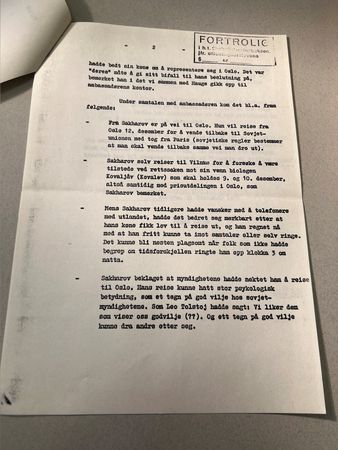

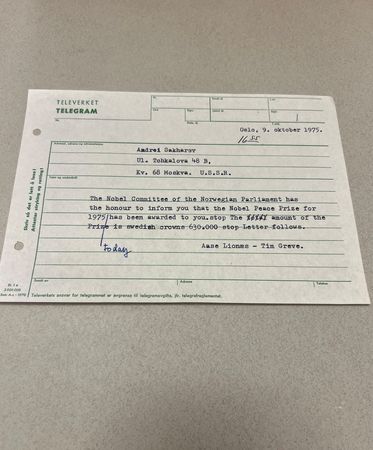

Authorities denied him the right to leave the country to receive the peace prize. Fifty years on, newly released papers reviewed by Reuters reveal for the first time how Sakharov smuggled the speech and his Nobel lecture to Norway.

Days before the award ceremony in early December 1975, Norwegian diplomat Viggo Lange took a phone call in Norway’s embassy in Moscow from “a Russian” eager to speak to him.

“It was Sakharov, asking whether he could come to the embassy before one o’clock,” Lange wrote in a memo to the foreign ministry back in Oslo. “He asked that someone met him outside in case he were prevented from entering.”

Lange recalls in the note: “Well before one o’clock, I went outside and stood on the pavement outside the embassy’s entrance.

“The (Russian) militia man in the street appeared to be waiting for something. After five minutes, he was called up and left, and about two minutes later, Sakharov arrived by chauffeured car (whose plates were MKZJ), which stopped on the other side of the street.

“Sakharov recognised me and I met him on the edge of the pavement on the embassy’s side of the street. The militia man studied us with interest but did not give signs that he would intervene,” Lange wrote.

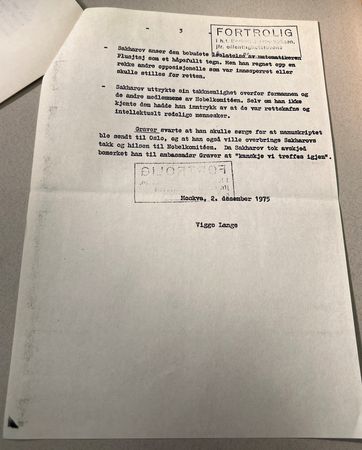

“Sakharov carried with him the typewritten manuscript for his Nobel lecture and his acceptance speech for the award ceremony.”

Lange then called Norwegian ambassador Petter Graver, who joined Sakharov in the embassy’s library. There, Sakharov asked Graver to ensure the documents be passed on to his wife, Yelena Bonner, who was in Western Europe at the time. Graver said he would, according to the memo.

‘STATE AND MILITARY SECRETS’

Bonner read her husband’s words at the December 10 ceremony in the Norwegian capital. In the speech, Sakharov stated that Soviet authorities had denied his trip to Oslo on “the alleged grounds that I am acquainted with state and military secrets”.

Sakharov was awarded the prize “for his struggle for human rights in the Soviet Union, for disarmament and cooperation between all nations”, according to the Nobel committee citation.

The process of nominations to the Peace Prize remains secret for 50 years and documents about the prize awarded to Sakharov were made available on request this year.

In 1980, Soviet authorities banished Sakharov to internal exile in Gorky, now Nizhny Novgorod, a city that was off-limits to foreigners, after his criticism of the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan.

Sakharov was released by Kremlin decree in 1986, after Mikhail Gorbachev came to power and introduced his policy of glasnost.

He and Bonner resumed their lives in Moscow. Sakharov travelled to the West, including Paris, resumed his scientific work and was restored to official good standing, before he died in Moscow on December 14, 1989.

(Reporting by Gwladys Fouche and Nerijus Adomaitis in Oslo; Editing by Ros Russell)