By Maggie Michael, Feras Dalatey, Reade Levinson and Maya Gebeily

DAMASCUS (Reuters) – The cries for revenge reached fever pitch on March 6.

Dozens of messages posted by various armed factions on social media, and shared with hundreds of thousands of Syrians, called for a “general mobilization” – or “al nafeer” – to help crush a fledgling insurgency by supporters of deposed and widely hated leader Bashar al-Assad.

Hundreds of pickup trucks full of fighters, as well as tanks and heavy weaponry, poured down major highways towards the coastal heartlands of the minority Alawite sect to which Assad belonged. They were seeking revenge against loyalists to the ousted president, mostly his Alawite former officers. Some of them had allegedly carried out a spate of hit-and-run attacks on the new military in an effort to stage a coup against the Sunni Islamist-led government.

Overnight and in the early hours of March 7, pro-government fighters fell on the neighborhood of Al-Qusour in the city of Baniyas, among the first major highway exits, opening fire on residential buildings and killing families in their homes. Similar attacks unfolded in a string of towns and villages further north along the coast including Al-Mukhtariya, Al-Shir, Al-Shilfatiyeh and Barabshbo where the ethno-religious Alawite community is concentrated.

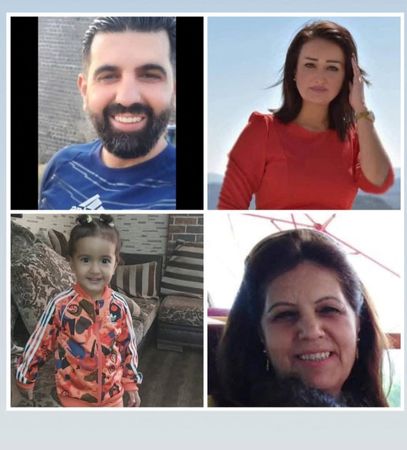

“I heard children screaming, gunfire, and my father trying to calm down the children,” said Hassan Harfoush, an Alawite from Al-Qusour who’s now living in Iraq, describing a phone call with his family before his parents, brother, sister and her two children were shot dead in the town on the afternoon of March 7, a Friday.

“My father was telling me: Pray for us. They’ve arrived.”

Harfoush said he’d left Syria months earlier following Assad’s ouster at the urging of his father who feared a wave of retaliation against Alawites: “He told me to at least have one of us alive.”

Within about six days, hundreds of Alawite civilians lay dead, according to Reuters reporting and several monitoring groups. Just three months after Assad’s ouster in December ended his brutal rule and almost 14 years of civil war, parts of western Syria had descended into vengeful bloodletting.

Reuters pieced together the events that culminated in the deadly rampage from interviews with more than 25 survivors and relatives of victims, as well as drone footage and dozens of videos and messages posted on social media.

The news agency was unable to determine if there was any coordinated plan by security forces to attack the Alawite enclaves or target civilians.

The Syrian government, which is now run by former members of the Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) rebel group, didn’t respond to a request for comment for this article.

Syria’s interim president Ahmed al-Sharaa denounced the mass killings as a threat to his mission to unite the country. He has promised to punish those responsible, including those affiliated to the government if necessary.

“We fought to defend the oppressed, and we won’t accept that any blood be shed unjustly, or goes without punishment or accountability, even among those closest to us,” he told Reuters in a previous interview this week.

While he blamed Assad loyalists for provoking the violence, Sharaa acknowledged that in response “many parties entered the Syrian coast and many violations occurred”. It became an opportunity for revenge for years of pent-up grievances, he said.

Reuters reached out for comment to several Assad loyalists who had posted messages online urging violence who didn’t respond.

Monitoring groups including Syria Network for Human Rights (SNHR) – an independent UK-based group – said over 1,000 people died in the violence, more than half killed by forces aligned with the new authorities and others by Assad loyalists. SNHR said the dead included 595 civilians and unarmed fighters, the vast majority Alawite. Reuters counted more than 120 dead bodies in at least six locations in the coastal provinces of Latakia and Tartous by geolocating videos posted to social media by residents, family members and the killers themselves.

The toppling of Assad, whose Alawite sect is an offshoot of Shi’ite Islam, saw the ascendancy of a new government led by HTS, a Sunni Islamist group that emerged from an organization once affiliated to al Qaeda.

Many of Syria’s Sunnis, who make up more than 70% of the population, felt politically and economically marginalized by Bashar al-Assad and his father Hafez, who both harshly cracked down on Sunni-dominated protests against their rule.

The new government is striving to integrate into its security forces dozens of rebel factions, born out of the long civil war. It relies on its own as well as newly recruited fighters in a group known as the General Security Service (GSS), other militias – including some foreign fighters – have been needed to fill a security vacuum left after the dismantling of Assad’s defence apparatus.

The mass killings were mostly carried out by gunmen from various factions aligned with the new government, including GSS, according to several of the witnesses. Video posted to Facebook and verified by Reuters showed some men in uniforms and arm patches similar to those worn by GSS participating in the violence in the coastal city of Jableh.

GSS did not respond to a request for comment.

A member of the GSS said he and dozens of other members of the unit had been deployed to the coast on March 6 with the mission of rooting out pro-Assad fighters, and returned to their base in Aleppo this week.

He said GSS fighters hadn’t targeted non-combatants as far as he knew, adding that the general mobilisation calls on social media had drawn in other undisciplined fighters who had killed civilians en masse.

“Anyone who had weapons joined,” he added.

‘STRIKE WITH AN IRON FIST’

Assad’s 24 years in power has left a toxic legacy after his escape to Moscow in December. Many among Syria’s Sunni community, which makes up the bulk of the population, harbour deep resentment at loyalists of the former president who have staged a low-level insurgency this month.

The temperature rose on March 6, when the government said that fighters led by Alawite former officers in Assad’s military staged one of their deadliest attacks yet, killing 13 members of the government-led security forces in Latakia province, a large Alawite centre. No one has claimed responsibility for the killings.

Reuters was able to review several messages calling for Syrians to head to the coast for the general mobilization.

For example, one Facebook page with more than 400,000 followers that says it is affiliated with GSS posted calls for Arab tribes in Syria to mobilize to support government fighters against Alawite insurgents. It also posted videos of armed groups sending fighters and vehicles to the coast to join the fight. Reuters could not immediately determine who runs the page.

Calls to arms also appeared in at least three WhatsApp groups each comprising hundreds of people in three different parts of northern Syria. The messages were localized, identifying specific meeting points in each area from which convoys would set off towards the coast.

On the same day, residents in major cities Damascus and Aleppo told Reuters they heard some Sunni mosques blaring out the calls for jihad on their loudspeakers. One imam at a mosque in Damascus denounced the alleged attack on security forces by Assad’s Alawite loyalists and called for Sunnis to take up arms against their sectarian enemies in a sermon broadcast on Facebook and seen by Reuters.

The Damascus imam, Mohsen Ghosn, didn’t respond to a request for comment via his Facebook page. Syria’s religious affairs ministry, which is in charge of all mosques, also didn’t respond.

Reuters was unable to determine how many fighters were mobilized to the cause. Drone footage of the highway east of the coastal city of Latakia, near the village of Al-Mukhtariya, shows hundreds of vehicles – including trucks with fighters in the back, some military vehicles and at least two tanks – were coming into the area in the morning of March 7.

The U.N. Human Rights Office told Reuters its inquiries indicated the mobilisation of fighters in support of the security forces included armed groups and civilians and happened very fast.

“Many of the attackers were unidentified as they were masked, and it is therefore very difficult to tell who did what. It was very chaotic,” a spokesperson said. “We don’t have a clear picture of the structure of the chain of command inside the caretaker government’s security forces.”

FIGHTERS GO HOUSE TO HOUSE

Al-Qusour neighborhood, where Harfoush’s family met with tragedy, saw some of the worst massacres, according to six witnesses and relatives of those slain.

One resident told Reuters fighters first fired heavy ammunition, artillery, and anti-aircraft guns at residential buildings. Shortly after, the militants began going house to house, killing civilians, he added.

The resident said about 15 militants stormed his home in three different groups, including some members of the GSS whom he identified by their uniforms as well as two Afghan fighters whose language he recognized.

Only his identity as a Christian saved him and his family, he said. One GSS officer had discouraged the other militants from killing them, he added.

The resident’s neighbours were less fortunate.

Two other Al-Qusour residents said several of their family members were killed. Another woman listed about 50 people she said she knew were killed, including her parents, their neighbours and the neighbours’ three-year-old child. A fourth resident said militants had dragged people from homes and killed them, including his 28-year-old nephew.

Fighters stole cars, phones and money from residents, forced women to hand over their jewellery at gunpoint and torched houses, shops, and restaurants, according to survivors.

Reuters was unable to independently confirm these accounts.

That same day, March 7, and in ensuing days, militants also descended on a string of towns and villages further north along the coast and in hills around the city of Latakia.

Reuters was able to verify footage of dozens of bodies lying in those villages that were shared online in the days after the killings.

One video posted online on March 7 showed the bodies of at least 27 men, many elderly, lying by a roadside in Al-Mukhtariya. On the same day in Al-Shilfatiya, a 20-minute drive away, the bodies of at least 10 people in civilian clothing were laid out on the ground outside a pharmacy and along the road, a video posted to Facebook and verified by Reuters showed. Many were still bleeding.

(Reporting by Maggie Michael and Feras Dalati in Damascus, Maya Gebeily in Beirut, and Reade Levinson and John Davison in London; Additional reporting by Eleanor Whalley, Fernando Robles, Mahezabin Syed, Inaki Malvido, Pola Grzanka, Sophie Royle, George Sargent and Milan Pavicic; Writing by John Davison; Editing by Pravin Char)