BEIJING (Reuters) -Unusually large quantities of antimony – a metal used in batteries, chips and flame retardants – have poured into the United States from Thailand and Mexico since China barred U.S. shipments last year, according to customs and shipping records, which show at least one Chinese-owned company is involved in the trade.

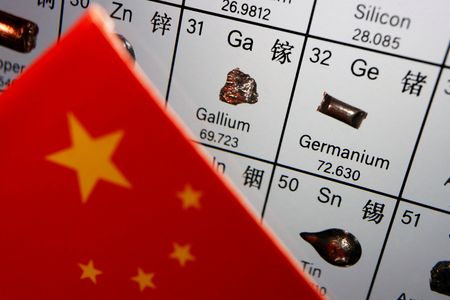

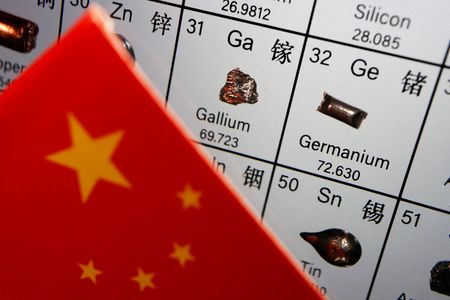

China dominates the supply of antimony as well as gallium and germanium, used in telecommunications, semiconductors and military technology. Beijing banned exports of these minerals to the U.S. on December 3 following Washington’s crackdown on China’s chip sector.

The resulting shift in trade flows underscores the scramble for critical minerals and China’s struggle to enforce its curbs as it vies with the U.S. for economic, military and technological supremacy.

Specifically, trade data illustrate a re-routing of U.S. shipments via third countries – an issue Chinese officials have acknowledged.

Three industry experts corroborated that assessment, including two executives at two U.S. companies who told Reuters they had obtained restricted minerals from China in recent months.

The U.S. imported 3,834 metric tons of antimony oxides from Thailand and Mexico between December and April, U.S. customs data show. That was more than almost the previous three years combined.

Thailand and Mexico, meanwhile, shot into the top three export markets for Chinese antimony this year, according to Chinese customs data through May. Neither made the top 10 in 2023, the last full year before Beijing restricted exports.

Thailand and Mexico each have a single antimony smelter, according to consultancy RFC Ambrian, and the latter’s only reopened in April. Neither country mines meaningful quantities of the metal.

U.S. imports of antimony, gallium and germanium this year are on track to equal or exceed levels before the ban, albeit at higher prices.

Ram Ben Tzion, co-founder and CEO of digital shipment-vetting platform Publican, said that while there was clear evidence of transshipment, trade data didn’t enable the identification of companies involved.

“It’s a pattern that we’re seeing and that pattern is consistent,” he told Reuters. Chinese companies, he added, were “super creative in bypassing regulations.”

China’s Commerce Ministry said in May that unspecified overseas entities had “colluded with domestic lawbreakers” to evade its export restrictions, and that stopping such activity was essential to national security. It didn’t respond to Reuters questions about the shift in trade flows since December.

The U.S. Commerce Department, Thailand’s commerce ministry and Mexico’s economy ministry didn’t respond to similar questions.

U.S. law doesn’t bar American buyers from purchasing Chinese-origin antimony, gallium or germanium. Chinese firms can ship the minerals to countries other than the U.S. if they have a license.

Levi Parker, CEO and founder of U.S.-based Gallant Metals, told Reuters how he obtains about 200 kg of gallium a month from China, without identifying the parties involved due to the potential repercussions.

First, buying agents in China obtain material from producers. Then, a shipping company routes the packages, re-labelled variously as iron, zinc or art supplies, via another Asian country, he said.

The workarounds aren’t perfect, nor cheap, Parker said. He said he would like to import 500 kg regularly but big shipments risked drawing scrutiny, and Chinese logistics firms were “very careful” because of the risks.

BRISK TRADE

Thai Unipet Industries, a Thailand-based subsidiary of Chinese antimony producer Youngsun Chemicals, has been doing brisk trade with the U.S. in recent months, previously unreported shipping records reviewed by Reuters show.

Unipet shipped at least 3,366 tons of antimony products from Thailand to the U.S. between December and May, according to 36 bills of lading recorded by trade platforms ImportYeti and Export Genius. That was around 27 times the volume Unipet shipped in the same period a year earlier.

The records list the cargo, parties involved, and ports of origin and receipt, but not necessarily the origin of the raw material. They don’t indicate specific evidence of transshipment.

Thai Unipet couldn’t be reached for comment. When Reuters called a number listed for the company on one of the shipping records, a person who answered said the number didn’t belong to Unipet. Reuters mailed questions to Unipet’s registered address but received no response. Unipet’s parent, Youngsun Chemicals, didn’t respond to questions about the U.S. shipments.

The buyer of Unipet’s U.S. shipments was Texas-based Youngsun & Essen, which before Beijing’s ban imported most of its antimony trioxide from Youngsun Chemicals. Neither Youngsun & Essen nor its president, Jimmy Song, responded to questions about the imports.

China launched a campaign in May against the transshipment and smuggling of critical minerals.

Offenders can face fines and bans on future exports. Serious cases can also be treated as smuggling, and result in jail terms of more than five years, James Hsiao, a Hong Kong-based partner at law firm White & Case, told Reuters.

The laws apply to Chinese firms even where transactions take place abroad, he said. In cases of transshipment, Chinese authorities can prosecute sellers that fail to conduct sufficient due diligence to determine the end user, Hsiao added.

Yet for anyone willing to take the risk, big profits are available overseas, where shortages have sent prices for gallium, germanium and antimony to records.

The three minerals were already subject to export licensing controls when China banned exports to the U.S. China’s exports of antimony and germanium are still below levels hit before the restrictions, according to Chinese customs data.

Beijing now faces a challenge to ensure its export-control regime has teeth, said Ben Tzion.

“While having all these policies in place, their enforcement is a completely different scenario,” he said.

(Reporting by Alessandro Parodi in Gdansk, Poland, Lewis Jackson in Beijing, Ashitha Shivaprasad and Sherin Elizabeth Varghese in Bengaluru; Additional reporting by Orathai Sriring in Bangkok and Pratima Desai in London; Editing by David Crawshaw.)