By Abigail Summerville

-Investment bankers had pitched a breakup to Kraft Heinz for years without success, sources said. The company finally agreed to a split when it realized that two simpler companies would be easier to manage and understand, garnering higher stock prices.

This strategy is gaining momentum in the world of food & beverage conglomerates.

The consumer food company’s separation into two – one focused on condiments like Heinz ketchup, the other on grocery food brands like hot dog maker Oscar Mayer – results from multiple points of pressure. But perhaps more than anything else, it reflects a changing view that bigger is not always better, because businesses with the most growth potential can get overlooked.

“Big guys have trapped value because they can’t buy something that moves the needle and do it right, or because they’re already too large,” said one consumer M&A banker.

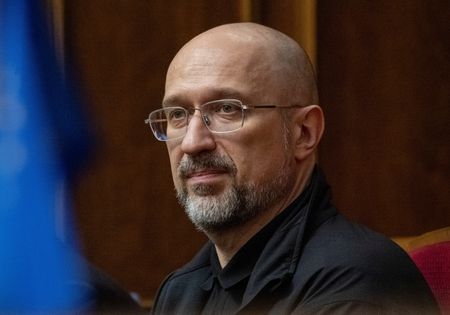

“The complexity of our business has impacted their ability to realize the full strength of our brands and operations,” Kraft Heinz CEO Carlos Abrams-Rivera, who is due to lead the grocery business, said on an investor call on Tuesday.

Kraft Heinz’s decision, announced on Tuesday, follows similar moves by peers.

Kellogg split up in 2023, renaming its snacks business Kellanova and the cereals unit WK Kellogg. Family-owned candy maker Mars bid $36 billion last year to acquire Kellanova. Ferrero made a deal to buy WK Kellogg this year.

Just last week, Keurig Dr Pepper announced plans to combine with JDE Peet’s and then separate its cold beverage and coffee divisions, citing differing growth profiles. And Unilever is spinning off and listing separately its Magnum-led ice cream business which includes popular brands such as Magnum and Ben & Jerry’s.

For bankers, the rationale behind these breakups is clear: focused, pure-play businesses are easier for capital markets to value and can pursue targeted M&A.

Since Kellanova and WK Kellogg started trading separately in October 2023, each company’s stock has gained around 20% and 27%, respectively, before news broke of their acquisitions. Kellanova fetched a 44% premium to its unaffected 30-trading day volume-weighted average price, while WK Kellogg’s premium was 40%.

Kraft Heinz has been trading at a price-earnings ratio of about 11, while more focused Mondelez and McCormick are in the low 20s. That dynamic has been part of bankers’ pitches to Kraft Heinz for years, sources said. Warren Buffett’s longstanding investment in the company through Berkshire Hathaway protected it from activist pressure to break up, but that faded when Berkshire directors left the board in May, the sources said.

Berkshire still owns around 27.4% of the company and Buffett on Tuesday told CNBC he was disappointed by the breakup.

Kraft Heinz declined to comment beyond the public materials released on Tuesday.

Breakup success is not guaranteed, though, and that has been the case especially since the COVID pandemic, according to research by JP Morgan. In a recent review, the bank looked at companies that split up and found that before COVID, price-earnings valuations generally expanded by 10%, to 9.9 from 9, compared with their parent firm. After COVID, the valuations fell by 5% to 10.4 from 11.

For food & beverage conglomerates, pressure is mounting to grow organically and drive volume in the face of changing consumer preferences away from processed foods.

Cost savings have long driven mergers, although the enthusiasm for the Kraft Heinz’s 2015 deal quickly faded, said another banker familiar with the company. “When Kraft Heinz came together, in that moment of time, the view was: we’re cutting costs everywhere. So all the organic investment in big consumer packaged goods almost bled out and moved outside the organizations,” the banker said.

Kraft Heinz’s decision reflects a broader challenge for large industry players. And M&A bankers said consumer packaged goods clients continue to ask if a separation is right for them.

“Now that we have a handful of examples, it could drive more traction with companies who have disparate portfolios,” a third banker said. “It’s been more challenging because consumers are truly behaving quite differently. There’s lots of active debate about what makes sense on the chessboard here.”

(Reporting by Abigail Summerville in New York; editing by Peter Henderson and Richard Chang)