By Aaron Ross and Maria Martinez

NAIROBI/BERLIN (Reuters) – They line up by the hundreds to meet recruiters at schools in provincial towns and convention halls in large cities, some carrying advanced diplomas, others with only a primary education to their name.

Each is hoping to land one of the million jobs the Kenyan government aims to fill this year in one of its most ambitious ever employment initiatives.

The jobs are not in Kenya. They are in rich countries in Europe, the Middle East and elsewhere, where officials hope young Kenyans can gain skills and income that will boost the domestic economy.

“There are no job opportunities here, so we are left with no option but to go outside Kenya,” said Lydia Mukii, a 27-year-old clinical psychologist who attended a government-sponsored job fair in the south-central town of Machakos, where recruiters distributed glossy flyers advertising pre-school teaching jobs in Germany and farm work in Denmark.

The fairs are part of Kenya’s first concerted effort to encourage labour migration to boost national development.

Sending workers abroad has been at the core of development strategies of Asian countries like the Philippines and Bangladesh for decades. But the approach has not been widely embraced in sub-Saharan Africa, where countries like Kenya have been accused by frustrated citizens of shirking their responsibility to create jobs at home.

That is starting to change. As fast-aging countries around the world search for workers to keep their economies afloat, some African nations without enough jobs for their rapidly growing populations are moving to take advantage.

“We have a very important resource called the human resource,” Kenya’s labour minister, Alfred Mutua, told Reuters in Machakos, where he launched a recruitment drive in November across Kenya’s 47 counties. “We can … export our labour and make a lot of money.”

For the government and jobseekers alike, the logic of turning to overseas employment is simple: about a million Kenyans enter the workforce each year, but only a fifth find formal jobs. Work in targeted countries pays considerably more than in Kenya, and part of the income is remitted to family members at home.

Central to the government’s calculus are stark demographic trends. The United Nations projects that Africa’s working-age population will grow by about 1.5 billion by 2100, and that by 2050, it will be the only region in the world with a falling ratio of dependents to working-age people.

Even so, the strategy is not without risks, including from a swelling backlash against immigration in many European countries and the United States.

In Germany, which signed an agreement with Kenya last September to relax certain requirements for employers who want to import skilled Kenyan workers, anti-immigration sentiment is rising, opinion polls show.

The coalition that agreed the deal now faces a Feb. 23 snap election in which its left-leaning parties trail in the polls behind right-wing rivals that have made tightening migration policies a centrepiece of their campaigns.

The centre-right Christian Democratic Union (CDU) and far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) party opposed a 2023 law intended to boost imports of skilled labour on which the agreement with Kenya was based, arguing that the law’s definition of skilled labour was too broad.

The CDU, whose leader Friedrich Merz is widely tipped to become the next chancellor, did not answer questions about its plans for the law and the Kenya agreement.

An AfD spokesperson, Rene Springer, said the law had been “disastrous” and should be “fundamentally reformed” to ensure only highly skilled professionals can immigrate.

Asked about Springer’s criticism, the governing coalition’s media department referred Reuters to the Interior Ministry. Henning Zanetti, a ministry spokesperson, declined to comment but pointed to statistics showing a nearly 15% year-on-year increase in visa issuances to skilled workers between October 2023 and September 2024.

Mutua was not concerned about Germany’s election, saying the country’s need for skilled labour would remain regardless of the outcome.

LABOUR SHORTAGES

There is no comprehensive data on the export of African labour abroad. But Mutua said Kenya’s government has facilitated the emigration of over 200,000 workers in the past two years and aims to export 1 million per year for the next three years.

Besides sponsoring job fairs, the government has been helping people with employment offers to apply for passports, complete background checks and obtain bank loans to cover travel expenses, he said.

It is also negotiating deals with other countries and working with vocational schools to tailor their courses to foreign labour demands. One university is now teaching sheep shearing with an eye to sending students to Australia.

Ethiopia, which introduced an online system four years ago to help match workers with vacancies overseas, aims to send 700,000 abroad in the year ending in July, seven times more than in fiscal 2023, labour ministry spokesperson Abebe Alemu told Reuters.

Tanzania said in November it intends to sign agreements with eight countries, including the United Arab Emirates, to send more workers abroad. The labour ministry and prime minister’s office did not answer questions for this article.

Some African governments see migration as a way to address unemployment that can lead to social unrest, such as deadly anti-tax protests that swept Kenya last year, analysts say.

Some richer countries, meanwhile, are coming to see formal labour deals as a better option than large irregular migrant flows, said Michael Clemens, an expert on the economics of migration at George Mason University in the United States.

“The question is: what is the alternative to this? Do you really think we’re headed for a world where, if you don’t make these agreements, migration is not going to happen?” Clemens said.

Some leaders have bowed to demographic realities. In Italy, home to the world’s second-oldest population, Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni’s right-wing government increased the number of work visas issued to non-EU nationals after campaigning on cutting immigration.

Sebastian Groth, Germany’s ambassador to Kenya, said his country was feeling the impact of skilled labour deficits estimated at up to 400,000 workers per year.

“We have restaurants and hotels in Germany that close on some days of the week just because they don’t have any waiters or chefs or hospitality experts,” he told Reuters.

He said the issue of importing skilled workers was often conflated with the hot-button topic of asylum seekers, which has dominated the election campaign since an Afghan asylum seeker was arrested in a deadly stabbing last month.

Even before a formal agreement was signed, there was growing cooperation on labour migration between non-government entities in Germany and Kenya.

Ian Kiprono, 26, is one of 14 Kenyan nursing students who came to Germany last April under a partnership between the Koblenz University of Applied Sciences and Mount Kenya University intended to help fill a projected deficit of 500,000 nurses by 2030. The students split their time between studying and working in a hospital in Bad Mergentheim.

“Germany is a nice place. The people are more friendly than what is known,” Kiprono said.

His biggest challenges have been the language and the weather.

“It’s very cold; we haven’t experienced that in Kenya,” he said, as a frigid drizzle fell outside the hospital’s glass facade.

POLITICAL BACKLASH

A growing body of research has shown long-term development gains from labour migration for sending countries, easing fears among some economists that the boost from remittances could be fleeting. But the politics are complicated in countries of origin too.

In Kenya, critics of the migration initiative accuse the government of failing to create jobs at home. Reports of mistreatment of migrants in some Middle Eastern countries, where millions of Africans already work, have also fuelled scepticism.

Mutua, whose social media posts about recruitment events often draw comments accusing him of promoting a “slave trade”, said formalising the process so the government can vet job proposals would better protect Kenyans from scammers and human traffickers.

Many Kenyans also fear a loss of skills needed at home. In the healthcare sector, for example, Kenya has less than a third of the 44.5 health workers per 10,000 people recommended by the World Health Organization, according to a labour ministry report from 2023.

Mutua said it made sense to send health workers abroad since the government did not have the means to hire them all.

Dennis Miskellah, deputy secretary general of the Kenya Medical Practitioners, Pharmacists and Dentists Union, disputed that argument. He said foreign hospitals tended to recruit the most skilled and experienced Kenyans, few of whom ever return home.

“Younger people are now losing out on teachers,” he said.

For workers hungry to go abroad, the path is still not easy.

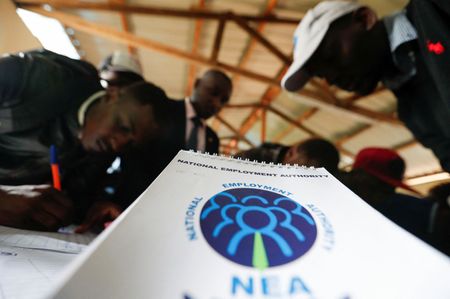

At the recruitment fair in Machakos, jobseekers started lining up under a hard rain at around 4 a.m. to register. They were then sent to classrooms to be interviewed by private recruiting agencies representing employers in about a dozen countries.

Nicholas Mutunga Mwongela, 52, showed up confident of his prospects, having worked as a freight operator in Saudi Arabia.

He received a provisional offer to work at a Polish meat processing factory for 24 zlotys ($5.87) per hour net but was disappointed to learn that the agency wanted around $4,000 to cover travel and other costs.

Two months later, he said he was trying to get a bank loan but first needed to find 160,000 Kenyan shillings ($1,240) for upfront recruitment fees.

Jane Mwangi, CEO of the Kenyan agency, AJW Africa, said it was important that jobseekers have “skin in the game”, and loans were available for most of these expenses.

Asked about agencies’ fees, the labour minister said it was up to jobseekers to find out the conditions of employment.

Mwongela remains optimistic.

“Once I get the money, I think I’ll be going,” he said. “I have the experience; I have the expertise; I have the exposure.”

($1 = 129.0000 Kenyan shillings)

($1 = 4.0893 zlotys)

(Aaron Ross reported from Nairobi and Maria Martinez from Berlin; Additional reporting by Maximilian Schwarz and Timm Reichert in Bad Mergentheim, Dawit Endeshaw in Addis Ababa and Nuzulack Dausen in Dar es Salaam; Editing by Alexandra Zavis)